Worth savoring for this historical novelist

of grace, intelligence, and style

of grace, intelligence, and style

I wanted to read Rachel Kushner’s Telex from Cuba (2008) after I’d liked her The Flamethrowers (2013) so much. I thought it was one of the best novels I’d read in the past decade. She writes big, taking on a subject, its era and locale, and then goes one step further to place it in an international

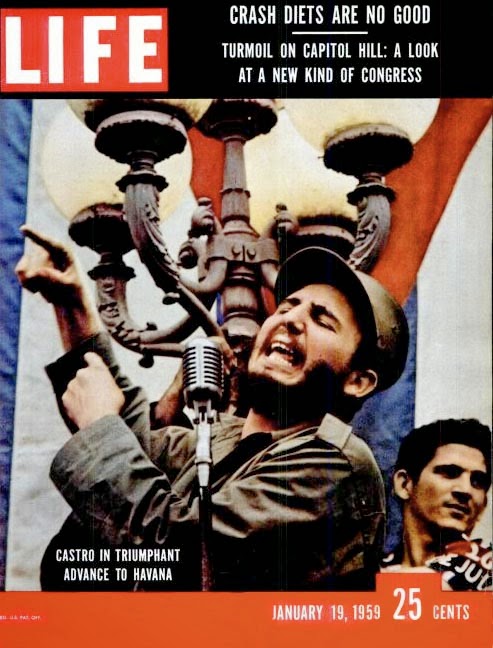

context. She did this with the art world of the 1970s centered in New York City before linking it to the American political radicalism of the 1960s and the European radicalism of the 1970s in Flamethrowers. In Telex, she recreates the American expatriate (or should I say late colonial) experience in Cuba during the 1950s from the waning presidency of Prio through the revolutionary ascendancy of Castro.

context. She did this with the art world of the 1970s centered in New York City before linking it to the American political radicalism of the 1960s and the European radicalism of the 1970s in Flamethrowers. In Telex, she recreates the American expatriate (or should I say late colonial) experience in Cuba during the 1950s from the waning presidency of Prio through the revolutionary ascendancy of Castro.

It’s a lot to bite off, especially in a novel that isn’t saga length (322 pages in the Scribner paperback edition). She uses multiple narrators in first person and third person limited omniscience so that the reader connects to specific parts of the story, rather than a grand, sweeping overview of history with an omniscient third person narrator. Because of this method, she then links the main events in the politically unsettled Cuba to a French agent provocateur that collaborated with the Nazis at the end of World War II and the eventual fate of many of the characters more than forty years after the overthrow of Batista.

|

| President Carlos Prio of Cuba |

|

| The United Fruit Company |

Many of the secondary characters, such as the Carrington family members, are intriguing, but none of the characters is as electrifying as the protagonist of Flamethrowers. She’s gutsy, though, in introducing Fidel Castro in a scene that’s extremely unexpected and bizarrely adult.

Where I think Kushner has to be reckoned a major (and potentially great) writer is in her style. It’s the golden literary arrow in her quiver. It’s elegant, seductive, and sometimes more informative than it may first appear. She sets out the main themes of the novel in her first paragraph when the seven-year old Everly sails toward Cuba with her family in 1952:

There it was on the globe, a dashed line of darker blue on the lighter blue Atlantic. Words in faint italic script: Tropic of Cancer. The adults told her to stop asking what it was, as if the dull reply they gave would satisfy: “A latitude, in this case twenty-three and a half degrees.” She pictured daisy chains of seaweed stretching across the water toward a distant horizon. On the globe were different shades of blue wrapping around the continent in layers. But how could there be geographical zones in the sea, which belongs to no country? Divisions on a surface that is indifferent to rain, to borders, that can hold no object in place?

No comments:

Post a Comment